Experts Ann Stott and Carla Torgerson answer L&D leaders' 8 most burning questions about evaluation, stakeholder relationships, and business results.

After an inspiring deep dive into the four critical skills L&D leaders need to keep their seat at the table in 2026, experts Ann Stott and Carla Torgerson sat down to answer the outstanding questions from the audience. The result: Actionable takeaways and a toolkit L&D leaders can use immediately to reinforce stakeholder relationships and speak the language of the business. Read on for detailed answers to eight of the most pressing questions facing L&D leaders this year.

Yes! We’ve compiled the following questions and mini-phrasebook to help you address both of these concerns. (Note: Please weave the questions into your conversations with stakeholders; do not treat them as a form or checklist.)

Their answers to these questions will help you create your value narrative and map learning outcomes directly to the business metrics your stakeholders value most.

Words matter. That’s why it’s important to speak our stakeholders’ language. Remember: Our stakeholders think in business signals, not competencies. Below are a few common phrases we use in the L&D world—and their translations into the business language that resonates with our stakeholders.

Learning Language

Skill development

Capability building

Knowledge transfer

Confidence

Business Language

Better (or faster) decisions

Fewer escalations

Reduced cycle time

Stronger customer conversations

Tell your stakeholders, “We’re not trying to train people—we’re trying to change what shows up in the numbers.”

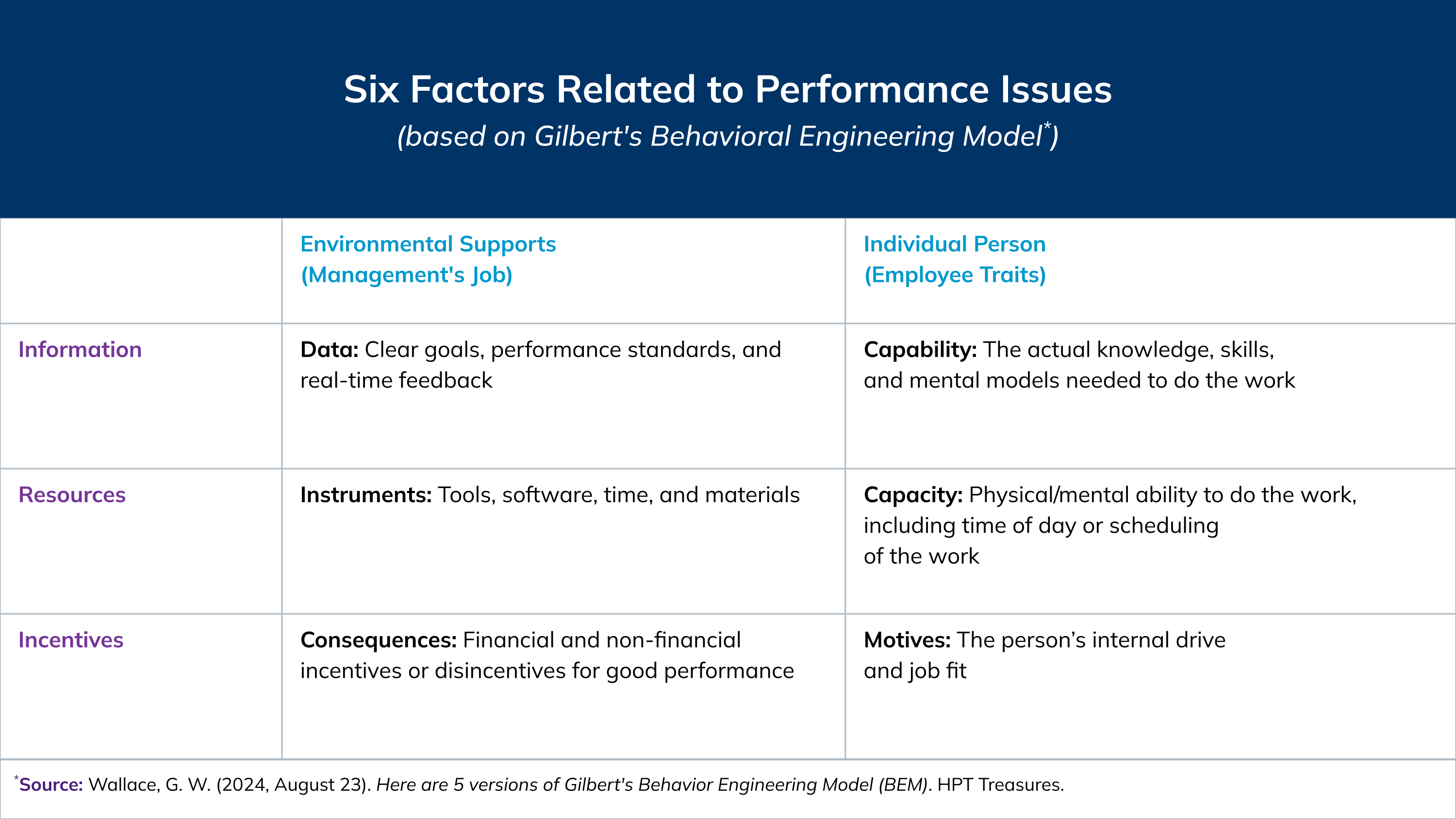

We should always start by asking our stakeholders about the business problem they want to solve. Revisit with them the six factors that can cause performance issues, and ask them to estimate a percentage value for each factor’s contribution to the problem they are trying to solve.

As learner advocates as well as business partners, this conversation offers us the perfect opportunity to remind stakeholders that a person’s capability is rarely 100% of the issue (or solution).

The SweetRush team likes to engage our client-partners in a whiteboard activity we call “Build the Box” to help shake out the factors contributing to a business problem. We list items such as budget, timeline, performance outcomes, and other project needs.

Then, we engage all stakeholders in a robust conversation to surface and document their goals for each component of the project. As a result of the activity, we identify any misalignment between stakeholders and any goals that may not be addressed by training and delve into deeper discussions about both.

“Was this training relevant to your job?” is a reasonable question—but it works best when the assignment is required, not optional.

When training is aligned to a business or compliance need, relevance is largely a design issue, meaning that:

If both of these statements are true, then training relevance should be high by default. So, low relevance scores signal an alignment problem, not a learner problem.

As you mentioned, determining the relevance of self-selected learning can be more complicated. That’s because, when learners have the freedom to choose their own adventure:

If training is optional and many learners answer that a training experience was not relevant to their job, it doesn’t automatically mean that the training was poorly designed or that the learner chose incorrectly.

Questions that lead us to a more useful framing of the relevance question in this situation include:

The real accountability question for L&D leaders and teams isn’t:

Did learners choose correctly?

Instead, it’s:

Did we help them choose intentionally?

That’s where better pathways and content guidance matter—especially in self-directed ecosystems.

The bottom line: Relevance is a strong metric when training is assigned for business impact. In self-selected learning, value shows up less in immediate relevance—and more in capability building, readiness, and future application.

Because Level 3 questions are focused on the behavior actually being performed, not just an intent to perform, the “how you will apply” question is still Level 2. (Following up with learners after the training experience and asking “Have you applied what you learned?” would be a Level 3 question.)

It’s true that confidence and predictive questions get us much closer to Level 3 than typical Level 2 knowledge-check questions and, as such, these questions yield insights that are more meaningful to the business.

Below are some examples of Level 2 questions that speak to the business by focusing on confidence and prediction of behavior. These can be used immediately after a learning experience:

Below are some examples of Level 3 questions (with one Level 4 follow-up) that speak to application. These can be used after employees are back on the job:

This example qualifies as Level 4: It goes beyond individual behavior change and reflects measurable business impact. The metric is:

To put it concisely: The behavior change itself is Level 3. The resulting time savings and increased sales activity at scale elevate it to Level 4.

When learning for headquarters (HQ) and learning for the field compete, field learning is often prioritized because the connection to business outcomes is more immediate and visible. Leaders can clearly see how it drives revenue, productivity, or customer results.

That doesn’t mean HQ learning is less important—it means its value isn’t always articulated in business terms.

The opportunity with HQ training has to be much more explicit about:

The real shift is reframing HQ learning from “support” to business enablement. When HQ programs are designed and measured around the problems they solve—risk avoided, decisions improved, execution accelerated—they compete on the same footing as field training.

So yes, field learning often wins on priority. The answer isn’t to fight that—it’s to rethink and redesign HQ learning so its business impact is just as clear.

When departments have competing priorities, the starting point isn’t fairness—it’s business impact.

We recommend prioritizing learning investments based on three criteria:

If a request doesn’t clearly tie to those three criteria, it doesn’t mean it isn’t valuable. However, it does mean that it may not be the right use of the organizational budget or limited employee time. In those cases, CLOs will often recommend that an individual learning team consider the initiative in their priorities and create the training for a specific team.

The most important step is alignment with senior leadership, which means getting extremely detailed about what is and isn’t a priority for the year.

That helps us create a clearer conversation down the road about tradeoffs: If we add X, which approved priority should we reduce or remove?

These conversations shift the decision from L&D saying “no” to leadership prioritizing and making intentional choices about where learning dollars go.

Got a question of your own about L&D strategy? Reach out to share with our experts!